Understanding Preventive Relief Under the Specific Relief Act With Real Examples

- Lawcurb

- Dec 23, 2025

- 16 min read

Abstract

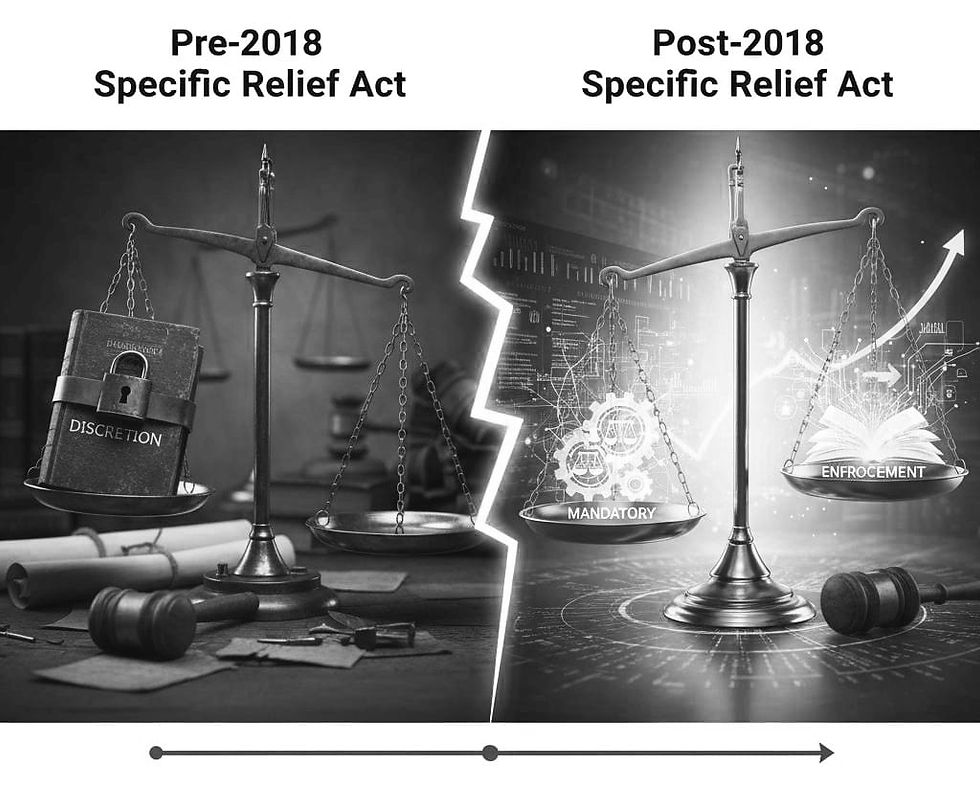

The Specific Relief Act, 1963, stands as a unique and vital pillar of the Indian legal system, providing remedies that are fundamentally different from the common law emphasis on damages. While compensatory damages aim to monetarily redress a wrong after its occurrence, the Act empowers courts to prevent the wrong itself or to enforce the actual performance of an obligation. This article delves into the proactive and equitable realm of Preventive Relief under the Act—a remedy aimed at stopping a threatened or ongoing wrongful act before it causes irreparable harm. Preventive relief, primarily in the form of injunctions, operates on the principle that "prevention is better than cure," especially where monetary compensation would be an inadequate solace. Through a detailed examination of the statutory provisions (Sections 36 to 42), foundational principles like ubi jus ibi remedium (where there is a right, there is a remedy), and the classic tripartite test for granting temporary injunctions, this article elucidates the nuanced framework of preventive relief. It further distinguishes between various types of injunctions—Temporary, Perpetual, and Mandatory—and explores specific applications such as injunctions for breach of contract, torts, nuisance, trespass, and infringement of intellectual property rights. The analysis is consistently grounded in real-world examples and landmark judicial pronouncements, illustrating how courts balance the protection of legal rights with considerations of equity, conduct of the parties, and the public interest. Ultimately, this comprehensive overview affirms that preventive relief is an indispensable instrument for achieving complete justice, upholding the sanctity of contracts, and protecting civil rights where damages alone would fail to restore the aggrieved party.

Introduction

The law of remedies is the bridge between a recognized legal right and its practical vindication. In the common law tradition, the default remedy for a civil wrong has historically been an award of damages—monetary compensation intended to place the injured party, as far as money can, in the position they would have been had the wrong not occurred. However, this remedy has inherent limitations. There are countless situations where money is a poor substitute for the actual subject matter of a dispute. For instance, no sum of money can truly compensate for the loss of a unique ancestral property, the destruction of an ancient heritage site, the continued violation of a personal right to privacy, or the irreparable market confusion caused by trademark infringement. It is in these scenarios that the doctrine of specific relief gains paramount importance.

The Specific Relief Act, 1963, which replaced the 1877 Act, codifies this doctrine. Its purpose is not to award compensation for a past wrong but to specifically enforce the obligations of a party, either by compelling them to do something they promised to do or by restraining them from doing something they promised not to do. The Act is thus divided into two broad categories of relief: Specific Performance (enforcing affirmative acts) and Preventive Relief (restraining wrongful acts).

Preventive Relief, the focus of this article, is the equitable remedy par excellence. It is governed by the discretionary power of the court, guided by settled principles of justice, equity, and good conscience. Its most potent and common form is the Injunction. An injunction is a judicial order directing a person to refrain from doing a particular act (prohibitory injunction) or, in rare cases, to perform a specific act (mandatory injunction). The core philosophy is interventionist and forward-looking: to prevent an impending injustice, to stop an ongoing injury, or to maintain the status quo pending the final resolution of a suit.

The significance of preventive relief in contemporary jurisprudence cannot be overstated. In an era of complex commercial contracts, volatile business environments, and heightened awareness of civil and intellectual property rights, the ability to obtain swift judicial intervention to stop a harmful activity is often more critical than the prospect of a damages award years later. It is a tool that protects legal rights from being rendered moot by the passage of time or the completion of a wrongful act. This article will provide a comprehensive analysis of preventive relief under the Specific Relief Act. It will explore its statutory basis, the essential conditions for its grant, its various forms, and its application across a spectrum of legal disputes, all illustrated with concrete examples to demonstrate its practical operation in the Indian legal landscape.

Chapter 1: The Statutory Framework and Core Principles

Preventive relief is primarily dealt with under Sections 36 to 42 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963.

• Section 36 introduces the concept, stating that preventive relief is granted at the discretion of the court by injunction, temporary or perpetual.

• Section 37 defines Temporary and Perpetual injunctions.

A Temporary (or Interlocutory) Injunction is granted for a limited period, until the disposal of a suit or until further court orders. Its purpose is to preserve the subject matter of litigation and prevent any alteration of the status quo that could prejudice the plaintiff's rights during the trial. It is governed by Order XXXIX Rules 1 & 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908.

A Perpetual Injunction is granted by the final judgment of a court. It permanently restrains the defendant from asserting a right or committing an act which would be contrary to the plaintiff's rights.

Sections 38 to 42 lay down the circumstances under which perpetual injunctions can be granted and the exceptions to such grants.

Core Principles Governing Grant of Injunctions (Especially Temporary):

Courts do not grant injunctions, particularly temporary ones, as a matter of course. The plaintiff must satisfy a well-established three-pronged test:

» Prima Facie Case: The plaintiff must demonstrate that there is a serious question to be tried. The claim must not be frivolous or vexatious. The court does not delve into the merits conclusively but must be satisfied that there is a probability of the plaintiff being entitled to the relief sought at the full trial.

» Balance of Convenience: This requires the court to assess which party would suffer greater hardship if the injunction is granted or refused. The court weighs the potential injury to the plaintiff if the injunction is denied against the potential injury to the defendant if the injunction is granted. The scales must tilt in favour of the plaintiff.

» Irreparable Injury: The plaintiff must show that the injury threatened is of such a nature that it cannot be adequately compensated in damages. "Irreparable" does not mean literally impossible to repair, but that the injury is so substantial or of such a character that monetary valuation would be insufficient or extremely difficult. Loss of goodwill, unique property, trade secrets, or personal reputation often qualify.

Furthermore, the plaintiff must come to the court with clean hands—their own conduct must be fair and lawful. Delay in approaching the court (laches) can also be a ground for refusal, as equity aids the vigilant and not the indolent.

Chapter 2: Types of Injunctions and Their Application

A. Temporary Injunction (Interlocutory)

This is a provisional remedy, a holding order. Its sole aim is to preserve the status quo ante (the state of affairs as it existed at the time of filing the suit) to ensure that the final judgment, if in favour of the plaintiff, is not rendered meaningless.

» Example 1 (Property Dispute): 'A' sues 'B' for declaration of title and possession over a plot of land. 'B' is threatening to erect a permanent structure on the land. If 'B' is allowed to build, even if 'A' wins the case after 5 years, restoring the land will involve demolition and immense cost. 'A' can apply for a temporary injunction to restrain 'B' from any construction activity until the title is decided. The status quo—the vacant land—is preserved.

» Example 2 (Breach of Contract): A software company 'X' has a contract with a key employee 'Y' containing a 12-month non-compete clause. 'Y' resigns and immediately joins a direct competitor 'Z'. 'X' files a suit for injunction to enforce the covenant. Alongside, it seeks a temporary injunction to immediately restrain 'Y' from working for 'Z' and sharing confidential information. If 'Y' is allowed to work during the lawsuit, the confidential information may be irreversibly leaked, and the non-compete clause's purpose defeated. The balance of convenience favours 'X' to prevent irreparable harm to its business.

B. Perpetual Injunction

This is a final relief, granted upon a full trial on merits. Sections 38 and 41 of the Act detail when it can and cannot be granted.

» Section 38: A perpetual injunction can be granted to prevent the breach of an obligation existing in favour of the plaintiff. The obligation can arise from contract or from tort/title to property.

» Where compensation is inadequate: If the invasion of a right is such that pecuniary compensation would not afford adequate relief.

» Where it is necessary to prevent multiplicity of proceedings: Where the wrongful act, if continued, would lead to a series of suits (e.g., continuous trespass or nuisance).

» Example (Nuisance): 'P' owns a house next to 'D's' factory. 'D' starts emitting toxic fumes and causing unbearable noise at night, severely affecting 'P's' health and enjoyment of his property. 'P' sues for a perpetual injunction. Damages may compensate for past harm, but they will not stop the ongoing nuisance. A single order of perpetual injunction is more efficacious than forcing 'P' to file repeated suits for damages for each day of nuisance.

C. Mandatory Injunction

While most injunctions are prohibitory, Section 39 provides for mandatory injunctions. This is an order compelling the defendant to perform a positive act to restore things to their former position or to undo a wrongful act. It is granted more cautiously than a prohibitory injunction.

» Conditions: The plaintiff must show: (a) a very strong prima facie case; (b) the injury is severe and cannot be compensated by damages; and (c) the balance of convenience is overwhelmingly in his favour.

» Example: 'A' and 'B' are neighbours. 'B', despite objections, builds a wall that encroaches 2 feet onto 'A's' land and also blocks 'A's' ancient light and air to his windows. A prohibitory injunction came too late as the wall is built. 'A' can sue for a mandatory injunction compelling 'B' to demolish the encroaching portion of the wall. The court will grant this if it finds the encroachment wrongful and that the obstruction causes substantial injury.

Chapter 3: Specific Situations for Grant of Preventive Relief

1. Breach of Contract (Negative Covenants):

Specific performance of affirmative promises in a contract is governed by Part II of the Act. However, preventive relief shines in enforcing negative covenants—where a party promises not to do something.

» Example (Non-Compete in Sale of Business): Dr. Sharma sells his famous dental clinic "White Spark" in Connaught Place, Delhi, to Dr. Mehta, along with its goodwill. As part of the sale agreement, Dr. Sharma covenants not to open a new clinic or practice within a 5-kilometer radius for 5 years. If Dr. Sharma, a year later, starts a new clinic 2 km away, Dr. Mehta cannot force him to work (specific performance of a personal service is barred). However, Dr. Mehta can successfully seek a perpetual injunction to restrain Dr. Sharma from violating the negative covenant. The goodwill he purchased is protected. The landmark case of Gujarat Bottling Co. Ltd. v. Coca Cola Co. reaffirmed the enforceability of such negative covenants in commercial agreements.

2. Tortious Wrongs:

» Trespass: Continuous or threatened trespass to property is a classic ground.

» Example: 'A' repeatedly parks his car on 'B's' private driveway despite warnings. 'B' can sue for a perpetual injunction to restrain 'A' from trespassing.

» Nuisance: As illustrated earlier, both private and public nuisance can be restrained.

» Example (Public Nuisance): A resident's welfare association can sue a municipality for an injunction to stop it from operating a garbage dumping yard in violation of environmental norms, causing health hazards to the locality (M.C. Mehta v. Union of India principle applied through civil suits).

» Defamation: While damages are common, an injunction can be sought to prevent a future or continuing publication of defamatory material. Courts are cautious here, balancing the right to reputation with the right to free speech.

» Example: If a former employee starts a website dedicated to publishing demonstrably false and malicious statements about his ex-company's products, and shows intent to continue, the company may seek an interim injunction to take down the site pending trial.

3. Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Infringement:

This is one of the most active areas for preventive relief. The harm from infringement—loss of brand distinctiveness, consumer confusion, erosion of market share—is often irreparable.

» Trademark: A registered trademark owner can get an ex-parte ad-interim injunction (without hearing the other side, in urgent cases) against a counterfeit goods seller to prevent flood of spurious goods in the market before a festival season.

» Example: Lux Industries Ltd. gets a tip that a unit in Gujarat is manufacturing counterfeit "Lux Cozy" innerwear. They can immediately file for a temporary injunction, coupled with an Anton Piller order (for seizure of goods) and a John Doe order (against unknown defendants), to raid the unit and prevent sale.

» Copyright: An author can restrain the unauthorized adaptation or distribution of her novel.

» Patent: A pharmaceutical company can restrain a generic manufacturer from launching a drug during the patent term.

4. Protecting Personal Rights:

Courts use injunctions to protect rights to privacy, against harassment, and to prevent bigamous marriages.

» Example (Right to Privacy/Against Harassment): In the digital age, courts have granted injunctions restraining individuals from posting intimate/private pictures or making defamatory posts on social media platforms. (X v. Hospital Z and subsequent cases have expanded this realm).

» Example (Preventing Bigamy): A wife, upon learning her husband is about to solemnize a second marriage, can seek an injunction to restrain him from doing so, as it would be a violation of her personal rights under matrimonial law.

Chapter 4: Grounds for Refusal of Injunction (Discretionary Nature)

The grant of preventive relief is not automatic but discretionary. Section 41 exhaustively lists situations where an injunction cannot be granted. Key grounds include:

» To Stay a Judicial Proceeding: A court cannot enjoin another court of co-ordinate or superior jurisdiction.

» To Restrain Proceedings Relating to a Criminal Offence: A civil court cannot stop a criminal prosecution.

» To Prevent the Breach of a Contract Not Specifically Enforceable:

» Contracts of Personal Service: You cannot force an employer to keep an employee or an employee to work for an employer. However, a negative covenant in such a contract (e.g., not to join a competitor) can be enforced.

» Contracts Requiring Constant Supervision: Courts are reluctant to grant injunctions for contracts whose performance needs day-to-day monitoring.

» When Equally Effi cacious Relief is Obtainable: If the plaintiff can be fully compensated in money, and the defendant is solvent, injunction may be refused.

» Conduct of the Plaintiff: If the plaintiff has acquiesced to the defendant's act, or has delayed unduly (laches), or has not come with clean hands (e.g., having himself violated the contract), the injunction will be denied.

» When it Would be Oppressive or Inequitable: If granting the injunction would cause disproportionate hardship to the defendant or a third party without a corresponding major benefit to the plaintiff.

» Example of Refusal (Acquiescence): 'A' sees 'B' starting construction on a land 'A' claims. 'A' watches silently for 6 months as 'B' spends crores of rupees completing the building. Only then does 'A' file a suit and seek an injunction. The court will likely refuse the injunction due to acquiescence and laches. 'A' had knowledge but slept on his rights, allowing 'B' to change his position.

Chapter 5: The Interplay with Other Legal Provisions

Preventive relief does not operate in isolation. Its procedural engine, especially for temporary injunctions, is Order XXXIX of the CPC. The principles of ex-parte orders, interim stay, and appointment of commissioners for local investigation are detailed here.

Furthermore, the remedy interacts with other statutes. For instance, in cases of commercial contracts of a specified value, the Commercial Courts Act, 2015 imposes stricter timelines and conditions for granting injunctions to prevent abuse and delay tactics.

In family matters, injunctions are sought under the relevant matrimonial laws (Hindu Marriage Act, etc.) to protect against dispossession or alienation of property or to prevent marital harassment.

Conclusion

Preventive relief, embodied in the judicial injunction, is the sentinel of civil rights and contractual sanctity in Indian law. It is a testament to the legal system's recognition that justice is not merely about quantifying past losses but also about proactively safeguarding future rights. The Specific Relief Act, 1963, provides a robust yet flexible framework for this equitable remedy, balancing the plaintiff's need for protection with the defendant's freedom of action and the overarching demands of justice.

The discretionary nature of the remedy ensures that it is not weaponized for oppression but is carefully calibrated based on a prima facie case, balance of convenience, and the risk of irreparable injury. From protecting a homeowner's quiet enjoyment to shielding a multinational's trademark, from enforcing a negative covenant in a multi-crore business deal to stopping online harassment, the scope of preventive relief is vast and ever-evolving.

Real-world examples demonstrate its indispensability. They show that without the swift, restraining hand of an injunction, legal rights can be eroded, business advantages lost, and personal liberties violated in ways that no monetary award can later rectify. As societal and commercial interactions grow more complex, the strategic importance of understanding and seeking preventive relief will only increase. It remains a powerful affirmation that in a just legal system, the law not only provides a remedy for a wrong but also possesses the foresight and the authority to prevent the wrong from occurring in the first place. It is, in essence, the legal embodiment of the timeless wisdom that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Here are some questions and answers on the topic:

Question 1: What is the core philosophy behind the grant of Preventive Relief under the Specific Relief Act, 1963, and how does it fundamentally differ from the remedy of damages?

Answer: The core philosophy behind Preventive Relief is the equitable principle that "prevention is better than cure." It operates on a forward-looking and interventionist logic, aiming to stop a threatened or ongoing wrongful act before it causes irreparable harm or renders a legal right meaningless. Its fundamental purpose is to maintain the status quo and avert an injustice, rather than to compensate for one that has already occurred. This stands in stark contrast to the remedy of damages, which is retrospective and compensatory in nature. Damages operate on the principle of monetary restitution for a wrong that has already been committed, attempting to place the injured party in the position they would have been in had the breach not happened. Preventive relief, primarily through injunctions, acknowledges that for certain rights—such as those involving unique property, personal liberty, reputation, or intellectual property—money is an inadequate substitute. It seeks to protect the very substance of the right itself, whereas damages only provide a financial proxy for its loss.

Question 2: Explain the three essential tests a plaintiff must satisfy to obtain a Temporary Injunction, and provide a real-world scenario illustrating their application.

Answer: To obtain a Temporary Injunction, a plaintiff must satisfy a three-pronged test established by courts. First, the plaintiff must establish a prima facie case, meaning they must show that there is a serious, non-frivolous question to be tried and that, on initial evidence, their claim appears likely to succeed. Second, they must demonstrate that the balance of convenience is in their favour. This involves the court weighing the comparative hardship or inconvenience that would be caused to the plaintiff if the injunction is refused against the hardship to the defendant if it is granted. The scales must tilt towards the plaintiff. Third, the plaintiff must prove that they will suffer irreparable injury if the injunction is not granted—that is, an injury which cannot be adequately remedied by an award of damages at a later stage.

A real-world scenario would be a startup company, "TechNovate," suing a former key employee for violating a non-disclosure agreement by joining a direct competitor, "RivalCorp," and threatening to share trade secrets. TechNovate would argue: (1) Prima facie case: The signed agreement and evidence of the employee's access to secrets establish a valid claim. (2) Balance of convenience: The harm to TechNovate from losing its competitive edge and confidential information far outweighs the temporary inconvenience to the employee of being restrained from a specific job. (3) Irreparable injury: Once trade secrets are disclosed, the damage is permanent and cannot be undone by money; the loss of market position and unique knowledge is irreparable. Based on this, a court would likely grant a temporary injunction restraining the employee from working at RivalCorp until the full trial.

Question 3: Distinguish between a Perpetual Injunction and a Mandatory Injunction with suitable examples. Why are courts more cautious in granting Mandatory Injunctions?

Answer: A Perpetual Injunction is a final order, granted after a full trial on merits, that forever prohibits the defendant from committing a particular wrongful act. It is typically prohibitory in nature. For example, after a full trial, a court may grant a perpetual injunction to a homeowner, restraining a neighbouring factory from emitting pollutants that constitute a nuisance.

A Mandatory Injunction, on the other hand, is an order that compels the defendant to perform a specific positive act to undo a wrong or to restore things to their original state. For instance, if a neighbour has already built a wall that encroaches upon another's land, the court may grant a mandatory injunction ordering the neighbour to demolish the encroaching portion of that wall.

Courts are significantly more cautious in granting Mandatory Injunctions, especially at an interim stage, because they are more drastic in nature. Granting a mandatory injunction requires the defendant to take active steps, often at substantial cost, before a final determination of rights. It essentially grants the main relief sought in the suit at a preliminary stage. Therefore, the standard of proof is higher; the plaintiff must show a very strong prima facie case that is "almost certain" to succeed, the injury must be severe and clearly irreparable, and the balance of convenience must be overwhelmingly in the plaintiff's favour.

Question 4: Discuss a situation where a court would refuse to grant an injunction for the breach of a contract, citing the relevant provision of the Specific Relief Act.

Answer: A court would refuse to grant an injunction to prevent the breach of a contract which is not specifically enforceable, as per Section 41(e) of the Specific Relief Act, 1963. The classic example is a contract of personal service. The law will not force an individual to maintain a personal relationship against their will. For instance, if a renowned chef is under an employment contract with a five-star hotel and decides to quit before the term ends, the hotel cannot obtain an injunction to force the chef to personally continue working. Specific performance or an injunction to enforce affirmative service is barred. However, the law distinguishes between affirmative and negative covenants. While the hotel cannot force the chef to work, if the contract contained a valid negative covenant stating the chef shall not work for any competing restaurant within the city for one year after termination, the hotel could seek an injunction to restrain the chef from joining a competitor. The injunction in that case is not enforcing the service but is enforcing the negative promise ancillary to it.

Question 5: How does the concept of 'Irreparable Injury' justify the grant of preventive relief in cases of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) infringement? Provide an example.

Answer: The concept of 'Irreparable Injury' is central to justifying preventive relief in IPR cases because the harm caused by infringement is often intangible, pervasive, and impossible to quantify accurately with money. In trademark infringement, for example, the injury is not merely lost sales but the erosion of brand identity, dilution of distinctiveness, loss of consumer goodwill, and long-term market confusion. Once a counterfeit product of inferior quality floods the market under a brand's name, the reputational damage is immediate and often irreversible; consumer trust, once broken, is hard to restore. Monetary damages calculated on past sales cannot capture this future and ongoing harm to brand equity.

An example is a company like "Bata" discovering a small-scale operation manufacturing and selling counterfeit "Bata" shoes in local markets. If Bata were to only sue for damages after the fact, it would be nearly impossible to calculate the full extent of lost sales, reputational harm from poor-quality counterfeits, and the cost of customer confusion. By the time a damages award is secured, the brand's reputation in that market segment may be permanently tarnished. Therefore, Bata would immediately seek a temporary, and later a perpetual, injunction to stop the manufacturing and sale altogether. The court recognizes that the injury—loss of unique brand reputation and consumer trust—is quintessentially irreparable, making the preventive remedy of injunction not just appropriate but necessary.

Disclaimer: The content shared in this blog is intended solely for general informational and educational purposes. It provides only a basic understanding of the subject and should not be considered as professional legal advice. For specific guidance or in-depth legal assistance, readers are strongly advised to consult a qualified legal professional.

Comments